MACBETTU

October 2021. Serbian National Theatre, Novi Sad

MAIN PROGRAM

MACBETTU

Sardegna Teatro / Compagnia Teatropersona (Italy)

Saturday, 16th October at 20.00

Serbian National Theatre, Novi Sad

Sardegna Teatro / Compagnia Teatropersona (Italy)

M A C B E T T U

by Alessandro Serra

based on William Shakespeare’s Macbeth

Direction, Set, Lights and Costumes Alessandro Serra

Sardinian translation and linguistic advising Giovanni Carroni

Stage Movements Consultant Chiara Michelini

Compositions for Pinuccio Sciola's Sounding Stones Marcellino Garau

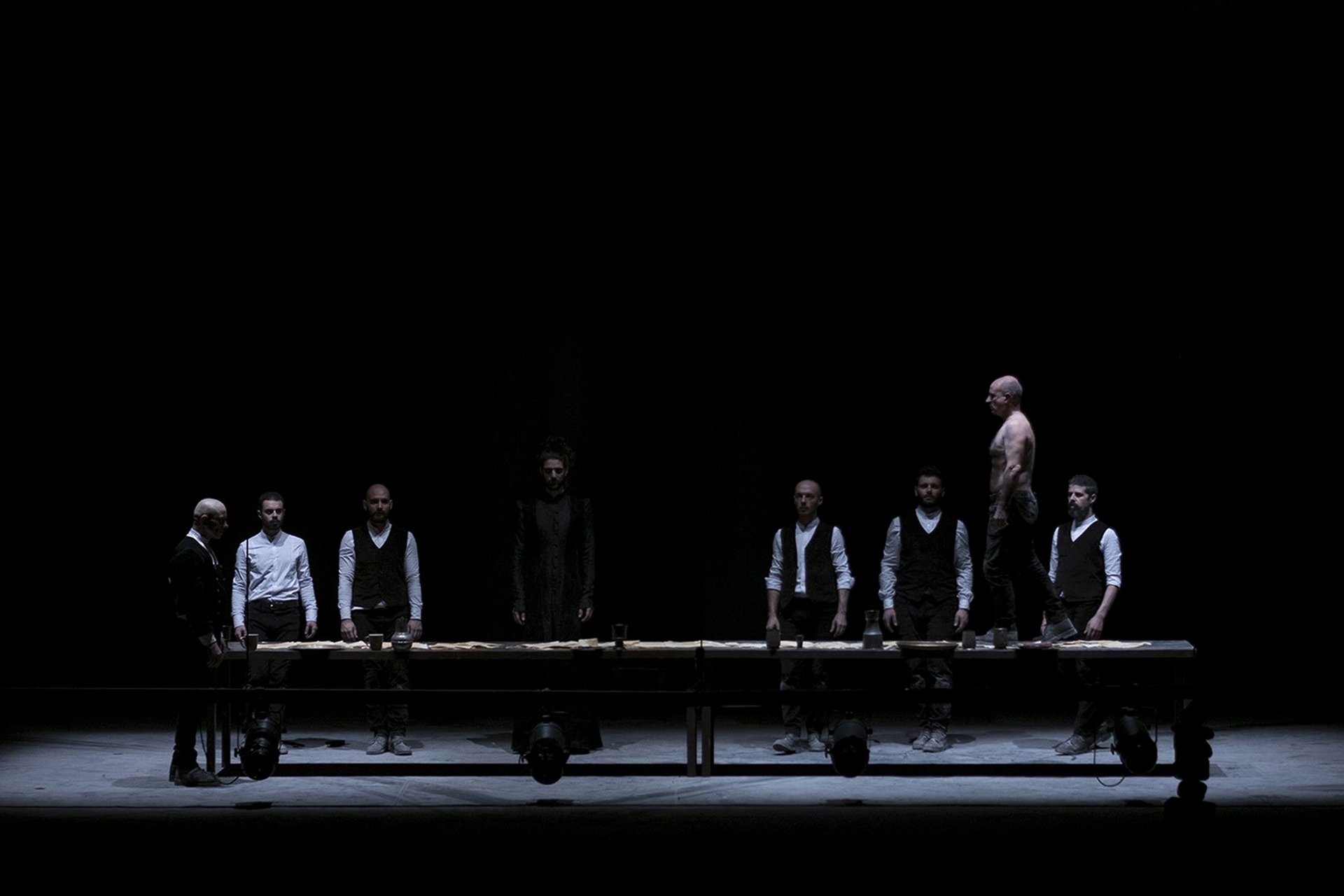

Cast Fulvio Accogli, Andrea Bartolomeo, Alessandro Burzotta, Giovanni Carroni, Andrea Carroni, Maurizio Giordo, Stefano Mereu, Felice Montervino

Production Sardegna Teatro

In cooperation with Compagnia Teatropersona

with the support of: Fondazione Pinuccio Sciola and Cedac Circuito Regionale Sardegna

Language: Sardinian with surtitles

Lenght: 90’

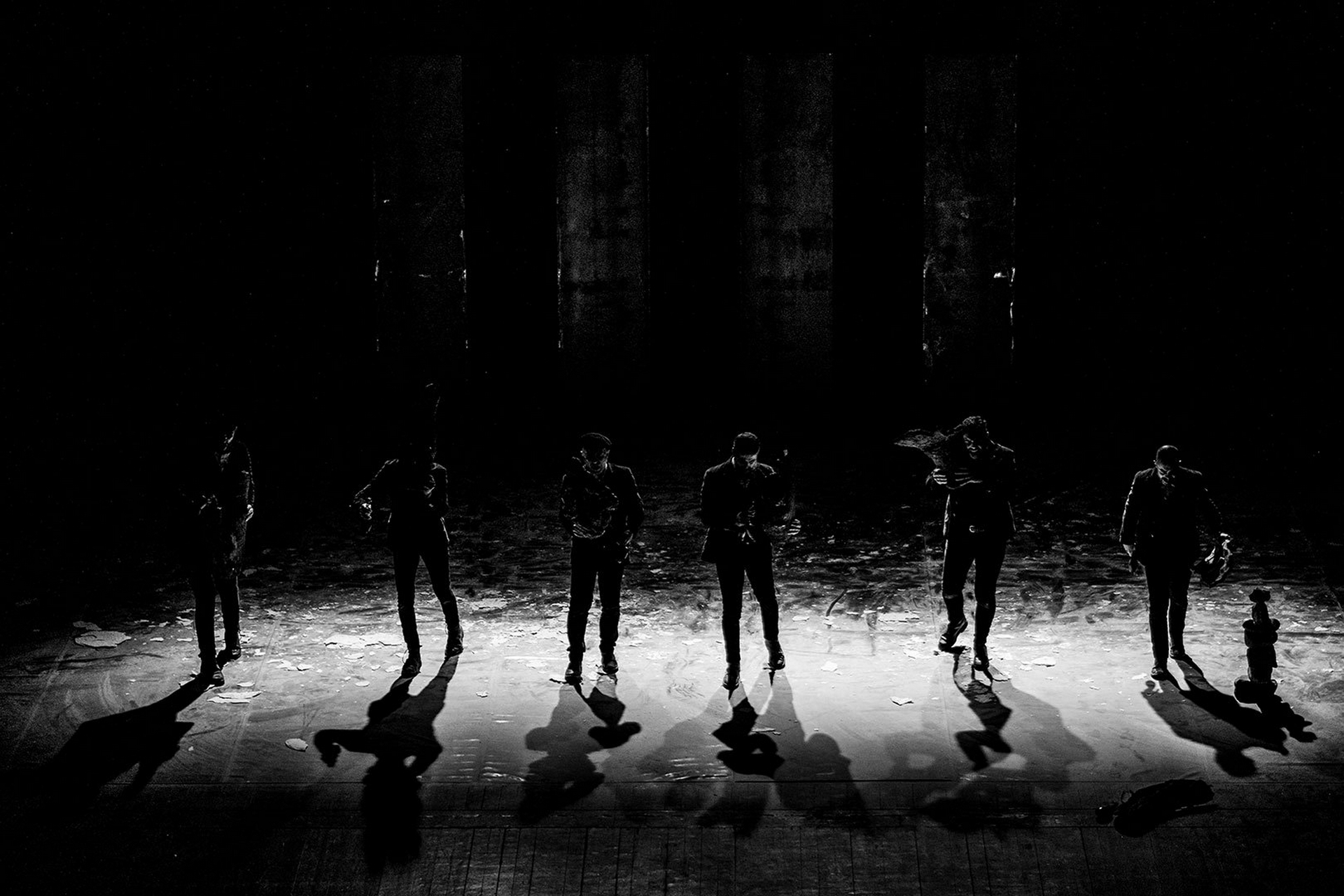

Shakespeare’s Macbeth, performed in Sardinian and, in the pure Elizabethan tradition, by an all-male cast. This is the project proposed by Alessandro Serra, founder and director of the Italian theatre group, Teatropersona. The idea originated in the course of Serra’s photographic coverage of the carnivals in Sardinia’s Barbagia region. The gloomy sounds of cowbells and ancient instruments, the animal skins, the horns, the cork. The power of the gestures and of the voice, the kinship to Dionysius and, at the same time, the incredible formal precision of the dances and chants. The sullen masks, and the blood, the red wine, the forces of nature tamed by man. But most of all the dark winter. Surprising are the number of analogies between the Shakespearian masterpiece and the variety of masks found in Sardinia.

The Sardinian tongue does not limit fruition, but transforms into chant what in Italian might remain mere literature. An empty playing space, animated by the bodies of actors that create settings and conjure up presences. Stones, earth, iron, blood, warrior stances, vestiges of ancient Nuragic civilizations. Matter that does not convey meanings, but primordial forces that act upon the receiver.

M A C B E T T U

by Alessandro Serra

Show of the Year – UBU 2017

Best Show 2017- National Association Theater Critics

Festival MESS Awards (Sarajevo):

- Best Director – Alessandro Serra

- The Golden Mask Award by Oslobodenje - Macbettu

- The Luka Pavlovic Award by theatre critics – Macbettu

MACBETTU

PRESS Quotes

Anu Ala-Korpela, AAMULEHTI NEWSPAPER, FINLAND

”Like From a Painting/The show radiates Sardinian masculine energy, its metallic set echoes frantic voices and its sceneries are like rough, beautiful paintings… Macbettu´s precision is as precise as it can get. It is imaginative… Macbettu creates beautiful images on stage”

(Four stars)

Anni Saari KESKIPOHJANMAA NEWSPAPER, FINLAND

”Macbettu is not based on dialogue alone, as visuality and movement expression play equally major roles in the whole. It is a complete artwork by Alessandro Serra that offers the spectator magnificently breath-taking visions.”

Anna Bandettini, LA REPUBBLICA

Very interesting, Serra’s performance, that translates Shakespeare’s tragedy into Sardinian and sets it an iconography inspired by the traditions of Sardinia. Above all, it is interesting because it is not a performance that sets off with the intention of subverting Shakespeare. On the contrary, it is rigorous and respects the original. The staging alludes to certain archaic sensations, a sort of primal nature of “Evil”, by way of the suggestive and the visual.

Graziano Graziani, MINIMA & MORALIA

The images of the performance possess a violent, archaic power, both beautiful and terrible the same time, and the Sardinian language (incomprehensible to me and to others) opens up a sonorous panorama that is no less dour and fascinating than the visible one. But, incredibly, what stitches these grim elements together is a subterranean irony, a chthonic and gothic hilarity that, for once, does not sabotage the drama, but tames it through comedy and exalts it. The supernatural element that pervades the tragedy is the terrain on which Sardinian ritual and Shakespearean ghosts can meet, transforming the masks of one tradition into a mirror in which one can observe the characters of the other. The result is a performance that is powerful and sombre, one that fascinates through its gloominess and surprises in its explosions of quasi-comicality.

Walter Porcedda, LA NUOVA SARDEGNA

CAGLIARI. Enthralling, visionary and apocalyptic. Like a Myth. It has evocative power as well as a contemporary sense of the tragic, recalling the wars displayed daily on televisions’ small screens, with their charge of mourning and tragedy.

Fernando Marchiori, ATEATRO

This Macbeth in Sardinian burrows deeply into the island’s most archaic strata, where it uncovers archetypes that are also germane to medieval Scotland – germane to us today. The eight interpreters are all male, honouring both the Elizabethan tradition and the carnivals of Barbargia, where the suggestions for Serra’s project originated years ago. Five of them execute a physical score rich in variations, dynamic array or single file, where each solo invariably renters into a harmonious whole. The remaining three are swathed in long, dark garments, with their black scarfs, handkerchiefs on their heads, giving life to a grotesque and extremely amusing trio of hunchbacked and quarrelling witches.

Teaser, photos, credits

http://www.sardegnateatro.it/spettacolo/macbettu

CONTACTS:

Aldo Grompone - International Tour Manager

+39 3358135885

MACBETTU. A VISIONARY AND ACOUSTIC WORK

Whatever is profound loves mask

Friedrich Nietzsche

The idea for Macbettu came about in February 2006 while shooting documentary photos of the Sardinian carnivals.

The gloomy sounds produced by cowbells and ancient sonorous objects, animal pelts, horns, and cork. Sullen masks and blood, red wine, the forces of nature tamed by man and above all the dark winter.

The similarities between Sardinia and Scotland are surprising as are Shakespeare’s masterpiece and Sardinian carnival characters and masks.

One image above all, the afternoon in which the Mamuthones filed through the streets of Mamoiada, I heard an ancient rhythm in the distance, an imminent force of nature about to strike relentlessly, placidly and unrestrainable at the same time: the forest was getting closer. A young child wearing an Issohadores mask reminded me of the crowned child who prophesizes that Macbeth will not be defeated until he sees Birnam Wood move toward the castle… the march of the Mamuthones.

A few days later I thought I recognized Banquo and Macbeth in two children that were fearlessly scrutinising their destinies in my camera lens.

And then the witches, the attitadoras of the Bosa Carnival; men dressed as old women in mourning imploring the audience for unu tikkirigheddu de latte (a drop of milk) between shouts and sardonic laughter accompanied by obscene sexual innuendos.

As in Kurosawa’s film Throne of Blood where the three witches are transformed into a single ghostly and pale Parca at the spinning wheel, the three Fates that weave Macbeth’s destiny are sublimated into the mask of the Filonzana, the mysterious and frightening old woman at the Ottana Carnival intent on spinning the thread of destiny.

In one week of photographic coverage, I couldn’t stop thinking about the possibility of translating Macbeth into Sardinian, and, in keeping with classical Elizabethan tradition, representing it using only male actors. The same men who impressed me greatly with the force of their gestures and voices, who had the confidence of Dionysius and at the same time the ability to perform traditional dances and songs with remarkable precision.

Folkloristic aspects apart, the costumes, masks, objects, sounds and songs were without a doubt the perfect means to express that tragic destiny. Sardinian Carnivals would be inoculated deep into the play, dissolving any deep-rooted ties and evident similarities immediately.

The Sardinian carnivals became a rich source to tap into for useful hints, indications with respect to the staging, creating a space for reciprocal contamination, where each simplistic representation of the drama is suspended giving way to something more fundamental: the revelation of tragic archetypes that prevail in Shakespeare’s characters as do the figures that come to life in the carnivals and perhaps in the viewers, too.

During rehearsals, the actors experienced all these elements, later eliminated through a process of distillation. The figures remain, delicate shells in which to infuse the souls of the characters and their respective emotions each time they are on stage, subtle traces, like the shadow of an aura.

Everything is soaked in blood, yet not a drop is shed.

The deafening noise of hundreds of cowbells is replaced by the subdued sound of sheep grazing in the night. The witches start to dance a ballu tundu before they hurl themselves into a vortex and vanish.

The masks dissolved into the iconic faces of the actors, later becoming cork bark where the knots look like eyes watching us. It’s grain sneers of war.

When I rewrote the text, I eliminated all the female roles but the story didn’t seem to suffer any deep trauma. I condensed all the women into a single mother goddess, bearer of death: Lady Macbeth. Taller and stronger than the men, just like one of the oldest representations found in Ozieri, slender, abstract, and transcendent: The 4000-year-old figure of a woman.

The Language

In Sardinian, the word is the thing itself

Michelangelo Pira

Macbettu is a work of visionary nature that presents a strong corporeal presence and physical actions, but above all it is an acoustic work for the power of its language and sounds.

For me, Sardinian has always been the language spoken in Lula and Bitti, my grandfather and my grandmother’s respective hometowns.

Macbettu speaks my father’s language.

It is the language I heard as a child and it seemed to emanate from the womb of the earth.

My grandfather called me, Cor’e manneddu! ( Grandfather’s heart)

He would read the Bible in Sardinian to me as if he couldn’t pray in the foreign language, Italian. Less than 10% of native Italians spoke Sardinian at the end of the 19th century.

Paul Celan once said: In a foreign language the poet lies. Actors lie when they recite a translated work by Shakespeare, striving to establish a rhythm that doesn’t belong to it.

So the question is: how does one turn something artificial into something spontaneous? How does one avoid the dystonia between the actors and the verses they recite?

The words must be pronounced by the actors, not by the characters: the actor is the one who must speak and sing.

For each play there is a different approach. In our case, Sardinian revealed itself as the perfect language. From the start, everything gushed forth, effortlessly. A living, rugged sound devoid of adornments and affectation. Even when it was read or recited by actors who weren’t familiar with a particular variant of the Sardinian language, a genuine bond was created with the text.

In Sardinian, a word is exactly what it means and when actors voice it genuinely, it hits the audience at full force. When this happens, the last thing on their minds is its significance.

Shakespeare’s works live beyond language, despite the treachery of translation.

Translations become out-dated, plays never do. In these, the language is merely one of the levels that allow the magic that instils life into each single moment of the story to be released.

For there is always a powerful underlying intertwinement: Macbeth has murdered the king.

But there is also living life, the mechanisms of human nature, the image: Macbeth has murdered sleep.

The mechanisms of the human soul are always perfectly orchestrated and are forever on the point of deflagration.

This is precisely why Shakespeare should always be rewritten each time one of his plays is performed, which leads us to the realisation that, in the end, the real author remains Shakespeare. His scripts are ardent matter, malleable and docile when challenged, powerful tools in the hands of directors and actors.

The language should be rewritten directly on stage. This can be fulfilled by the dramaturg or director or better yet by the actors, and that is why I decided to entrust the translation to an actor, Giovanni Carroni, with whom from the start we began working on the songlike aspect and not on the literature.

To say, not to recite, seeking the vitality of the spoken language.

The sound of the language is vehicle to the image. It is not about meaning but about the forces that come into play when the sounds are uttered.

Thanks to this experience, I was able to verify what Pasolini meant when he wrote:

In theatre, words are twice glorified: they are written, as in the pages of Homer, but also spoken as happens between two people at work: there is nothing more wonderful.

The Supernatural

When the supernatural enters a being that does not have enough love to receive it, it becomes evil.

Simone Weil

Macbettu grabs the witches by the head and orders them to speak.

The witches predict a bright future for Macbettu - thou shalt be Cawdor, then King – just as spring is propitiated during the gloomy Sardinian carnivals. The witches’ prophecies immediately come true; Macbettu becomes Thane of Cawdor. the supernatural enters into him

If chance will have me king, why chance may crown me

Without my stir.

And yet he yields to temptation.

He murders the King and anyone who gets in his way or destiny.

The witches are forces of nature and as such they predict a glorious future for Macbettu. There is no evil in them but in those who do not know how to receive transcendence.

Objects and Costumes

Except for ancient stones, one does not look for auras in the Western World

Elémire Zolla

Objects have a life of their own. They are not there by chance. They act, and in this sense are symbols. Their value lies not in their meaning (as in the poverty of symbolism) for they are not meanings, but forces that act on those who receive them. In Macbeth, the stark stage of Elizabethan theatre is lead to the culmination of ritual practices in which Dionysus is incarnated in an empty space.

Sardinia is a vast floating rock. While exploring it, one sees nuraghe, the tombs of giants, pinnette, and menhirs. I decided to use stones as the primary elements as well as iron, cork and wood. Particularly the stones the guards use as pillows, as would shepherds to keep from falling asleep while watching the flocks, or bandits, who used them for a light sleep. Stones that fall, roll, and placed precariously one on top of the other with each murder.

In addition to stones, cork, cowbells, the leppa, a traditional Sardinian knife, symbol of the tragic, common to both the Shakespearean drama and the carnival.

In fact, the central vision of Macbeth is his first hallucination: a bloody dagger suspended in mid-air.

The sharp dagger is also the weapon evoked by Lady Macbeth:

Come, thick night,

And pall thee in the dunnest smoke of hell,

That my keen knife see not the wound it makes,

Nor heaven peep through the blanket of the dark

To cry, ‘Hold, hold!’

With regards to the costumes, we did a great deal of research into an immense heritage of extraordinary beauty. My grandfather used to wear the traditional black velvet three-piece suit. The white shirt is worn as a neutral surface onto which the spectator can project the various characters with extreme ease. The witches wear the traditional female costumes of the carnivals, attitadoras and the filonzana. The only exception is Lady Macbeth who wears a neutral black velvet costume.

The sounds

Like the sound of bells, in whose peeling you may find any name and word you choose to imagine

Leonardo Da Vinci, Treatise on Painting

We dealt with sound as we did with language and the images. They act upon those who see them and those who hear them. They signify nothing.

The emotions they transmit belong to humanity and as such they resound in those willing to listen to them.

Sardinia has a wealth of songs, music and musical instruments of incomparable beauty.

During rehearsals we experimented with polyphony but only to hone our capacity for listening.

We can allow ourselves to do away with wordy dialogues narrating the ambush on Macbeth if we succeed in transforming the harsh sound of the approaching bells - that originally made me think of the forest - into a soft sound, such as that of sheep grazing in the night or of warriors clad in metal armour attempting to remain noiseless so as not to arouse the enemy.

The musical texture is entrusted to the scenes and actors. Matter sings, one must only know how to listen to it.

Such as the carasau bread that crumbles beneath Banquo’s steps, like shattered bones, destiny knocking on the rusty door of hell, ashes falling, the banquet mugs like sharpened blades, the subdued and menacing sound of sheep bells with their shinbone clappers. Bones, rolling stones, the whispered voices of the witches singing the attittidu for the dead and curses for the living.

The only only exception: Pinuccio Sciola’s sounding stones

The voice of Sardinia, it’s past silenced for millennia.

To make them sing, his stones must be caressed, never struck. A humble gesture, never commanding, like the gentle rubbing when conjuring up genies. A touch that Macbeth does not have, wont as he is to knocking forcefully and demanding that his destiny be fulfilled.

The hallucinations are accompanied by the liquid sound of limestone.

Liquid because it restores the memory of water that in fossilising has become stone.

Duncan’s death and his shriek from the afterlife and the gloomy sounds of the limestone, reviving its memory of fire and lava. Knocking from the bowels of the Earth that turns into a chilling banging at the castle’s door.

For us, the sounding stones were fundamental in understanding how to make its original image emerge from the text, its original voice.

The sound that Sciola extracted from the Sardinian stones whispers to the senses of he who listens to them, the millennia-long memory of Sardinia.

And there is nothing to understand.

Alessandro Serra

Curriculum Vitae Alessandro Serra

Ingmar Bergman’s practice of transcription for the scene represents Alessandro Serra’s first approach to the theatre. He trains as an actor studying phisical actions and vibrating singing - as in the Grotowski’s tradition – and then gets to the objective laws of moving, written down by Mejercho’ld and Decroux. Since he was young, he practices martial arts and using it as a complement to his theatral training. In the meanwhile he graduates in Arts and Performing Studies at Sapienza University of Rome, with a dissertation on the Image Dramatugy. The meeting with Yves Lebreton and his Physical Theatre during his studies was crucial for his shaping. In 1999 he founds Compagnia Teatropersona, with which he starts staging his scripts, creating heads and sets up scenes, costumes, lights and sounds by his own. Between 2006 and 2011 his research on scene as a pure material results in a “Silence Trilogy” (Beckett Box, Trattato dei Manichini e AURE), in which dramaturgy is practised as a real removal of aureas from the S.Beckett, B. Schulz e M. Proust’s literary works. In 2009 he makes his first play for kids, Il Principe Mezzanotte, showed more than 200 time, in Italy and abroad. In 2013 his play Il Grande Viaggio – play tout public – is about immigration. During 2015 his theatral research approaches the dancing language, hence L’ombra della sera, dedicated to the Alberto Giacometti’s life and the work. In the same year - in collaboration with the Accademia Arte della Diversità’s actors – he creates H + G. In 2017 he comes back to the straight theatre and stages MACBETTU, produced by Sardegna Teatro – Theatre of Relevant Cultural Interest, and FRAME, dedicated to the Edward Hopper’s world. With his company Teatropersona he toured his shows in Italy, France, Switzerland, Korea, Russia, Spain, Bulgary, Poland and Germany.

Sardegna Teatro is the first theatral institution using the easy reading Font ©Biancoenero

english

english  srpski

srpski